By Diana Bourel,

transpersonal therapist and yoga instructor.

“Relationship”, a shiatsu therapist once told me, “is the last great human frontier.”

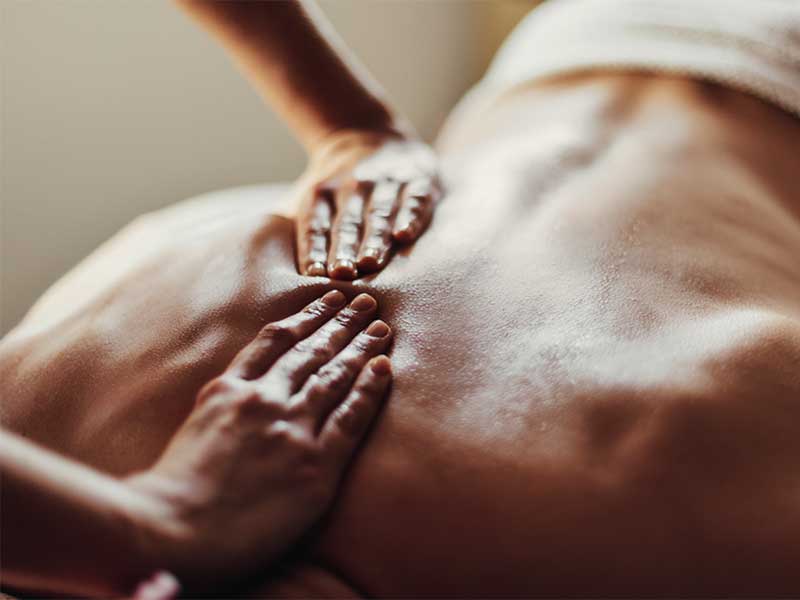

He was working on a pressure point somewhere between my shoulders as he spoke. Moments later, I was crying. A memory had bubbled to the surface under his skilled touch, and there I was, decades back in my own childhood.

I was remembering the promise I had made myself after I was sent to Ecuador to live with my grandparents while my parents, still college kids, got their financial bearings. Being so far away from my US-residing parents was like being banished from any possibility of happiness. Long- distance loving was excruciatingly painful for the little person I was.

“I’ll never love that much again!,” I vowed, and for that moment, it made me feel better. It made me feel that I was in control and that I could decide when and how and to what extent my heart would open, indeed, if it would open. No being vulnerable for this spunky kid!

Since then, I have revisited my passionate vow to become dispassionate. How measly it seems now, how childish. Did I really think I could place ceilings on how much to love, or that I could

regulate the flow of this vital energy by exercising some volitional crank? Did I really think that I could spare myself the ecstasy of experiencing the cup Love held to my lips? Or the devastating hollows of seeing it removed?

Well, frankly, yes.

At times, that is exactly what I thought.

Still today, managing emotional pain and developing a reliable and centered psychic m.o. in times of (di)stress can be a real issue.

Tragedy, trauma or disappointment each hold out a real invitation to feel, to experience, to grow, but when spinning, I sometimes take the only self-serving, self-preserving option I see.

Counter-intuitive as it might be, it is to shut down and recoil and run for the hills and shut the door behind me and pretend that no wonderful or terrible thing was behind the wild thumping of my heart.

Some ferocious, proud and angry part of me does not want the world to see how hurt I was, or that I was crying. Pain like that is a private matter. There I would be, as a child, then as a teenager, now a woman, shaking my fist at the mountain, cursing the heavens and feeling every bit a fool. “Duped again!” I would lament, practically spitting out the bitterness of the curse, wrestling with an intellect that had already turned its back on me.

Being responsible for the love that has been placed in me is a rather formidable challenge, not the least of which is the arduous task of staying present and aware that it exists.

Distractions and emotions, self-judgment, addictions and attachments are constantly undermining my ability to stay the course. Sometimes it is the fatigue of standing strong, or the sheer weight of gravity that leads to my undoing.

Sometimes, it is my eyes and heart that become too laden with loss to peer into the next dawn. Collective inner voices tug, chiding me with the reprimands of failures past and back-brain survival concerns, herding me within the parameters of social mores to which I must strictly adhere, forfeiting curiosity or questioning in the process.

“What is so great about being aware, or loving?”, these voices query. “Is it really all it is cracked up to be, and what is in it for numero uno? “

Perhaps the most intriguing thing about increasing the capacity and space that consciousness requires is that above and beyond any personal gain, I can become a better citizen of the world. I can move beyond my small self and become part of a bigger world.

When I decided to pursue a scuba diving certificate, I had a personal goal in mind. I did not want to be daunted by 75% of the element that composes the Earth. The first two dives were defined by my limited awareness and a certain apprehension that I would suffer from hypothermia. The dive gear was uncomfortable. The water was a little too cold, and more agitated on the surface than I would have liked. I felt doltish. My mind whirred. Was this supposed to be relaxing? My teacher took my hand, and led me and another student, a diffident German pilot, under water. At first, I could concentrate only on the instructor’s hand, and the necessity of staying close to him. My eyes widened and narrowed, like the aperture of a camera. Ooo, look at the amazing colors of those fish, eyes wide, ooo, look at that suspicious looking barracuda, eyes narrow.

By my third or fourth dive down, something shifted. I became interested in my surroundings, notably, those beyond the confines of my small person. I began to apply some of the diving

practices that good buddies are responsible for providing: verifying air levels in tanks, watching carefully to see what fellow divers found interesting or were wordlessly trying to share with me. By the third or fourth dive, I became confident, discarded my fear, and really began to absorb what I was seeing. As I became less fearful, I became more effective and improved my diving skills. As I moved beyond, if only partially, from my own sphere of limitations, I became more available to others, more caring, and more reliable.

Is this common?, I asked the instructor, or is my experience unique? Birdie, who has thousands of dives to his credit, says that he has observed the shift in apprentice divers hundreds of times. Though relationships, particularly new ones, are like a strange new environment in which we must learn to swim and survive, they provide an ocean of opportunity for healing. They provide the parameters for deep change. They allow us to develop our hidden talents, and hone our ability to stay present, alert and attentive. They allow us to look past the fearful ego into the more generous Self. Feelings allow us to listen to one another, to check our vital signs, and to be both in and of the world deeply and fully. There is no question that fear can be a device for getting us into the present tense of a relationship (fear of being alone, fear of being loveable, or good enough, fear of loss) but ultimately, it is love and applied awareness that keeps us there.